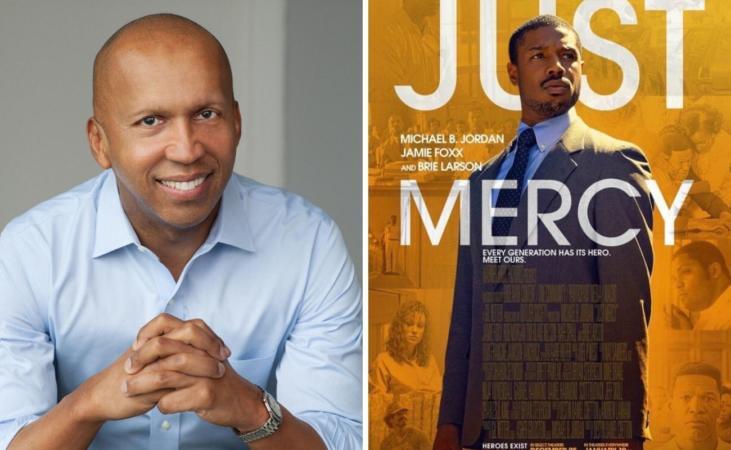

Attorney Bryan Stevenson is trying to tell us something.

One of the greatest civil rights leaders of our time, Stevenson’s life’s work has been to defend the indigent and condemned through the legal system. His New York Times best-selling book Just Mercy, which details his life and his fight for justice for his clients over a 30-year career, has now become a Warner Bros. feature film, premiering on Christmas day and starring Michael B. Jordan as Stevenson.

The film narrows in on the founding of Stevenson’s nonprofit law firm and human rights organization the Equal Justice Initiative, and two of his clients on death row in Alabama. In stellar supporting roles, Jamie Foxx and Rob Morgan revive the two clients, Walter McMillian and Herbert Richardson, respectively.

McMillian was wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a white teenage girl as punishment for having an affair with a white woman. Richardson was a Vietnam War veteran who struggled with PTSD. He put a bomb on a woman’s porch that exploded and killed a young girl. Stevenson fought for both men to be removed from death row.

“Initially there was some back and forth about [whether Herbert’s story would be included in the film],” Stevenson told Shadow And Act. “But it was really important to me that we also have characters and clients who were not factually innocent in the way that Walter McMillian was, because I wanted people to understand that this question of justice isn’t only about justice for the innocent.”

As Stevenson writes in his book, “The power of just mercy is that it belongs to the undeserving.”

A Radicalizing Trauma

The mercy that Stevenson advocates for on behalf of children sentenced to life in prison and people incarcerated on death row stems from his proximity to and sense of community with the condemned.

In the film, a young Stevenson explains to his mother why he, a Delaware-born, Harvard Law School-educated Black man, is choosing to be a lawyer for poor, mostly Black men on death row in Alabama. Jordan says in the scene, “It could’ve been me, Mama.”

Both Stevenson’s book and the film recount how his Harvard Law degree and his suit and tie couldn’t protect him from police officers who held him at gunpoint for no legal reason. His Bar admission, class privilege and mastery of Standard English didn’t stop a prison guard from subjecting Stevenson to the same dehumanizing strip search that incarcerated people are forced to endure when they first enter prison.

The message of Just Mercy to Black people is clear: In a white supremacist society, Blackness—no matter how educated or upwardly mobile—is not up for negotiation. At any time, any of us could be the victim of police brutality, the wrongfully accused, the condemned. With that baseline understanding, we are empowered to invest in the well-being and the future of those who are poor, those who are incarcerated, those who are on death row. It could’ve been me.

The radicalizing trauma that moved Stevenson toward defending and protecting those experiencing poverty and lacking access to legal resources and representation may come as a surprise. When he was 16 years old, his grandfather was murdered by children after he refused to let them steal his 13-inch black and white TV.

“When my grandfather was murdered, it first of all made me think a lot about the problem of violence and criminality and what that does, but it was also kind of disruptive to imagine that he could have been killed by young kids,” Stevenson told Shadow And Act. “It just created all of these questions. And my grandmother was someone who wouldn’t accept just a punishment response. She was more interested in why. ‘Why are there children living in a way where this is something they would even consider doing?’ And the question of why and how differently some people are living and what circumstances give rise to this kind of behavior became the spark that lead to this path,” he said. “I didn’t know then that I’d want to be a lawyer but…it certainly sensitized me to the tragedy of people living such desperate lives that they would engage in the kind of gratuitous violence that my grandfather [experienced].”

That sensitivity has led Stevenson to fight for and win relief for over 135 people who were wrongfully convicted on death row. He’s also won several Supreme Court cases, including a 2019 ruling protecting people in prison with dementia from death row and a 2012 landmark ruling banning mandatory life-without-parole sentences for all children under 18.

A Harrowing History

The relief he’s won for hundreds of other clients who were unfairly sentenced or wrongfully convicted is just the beginning of his work. A professor at New York University School of Law, Stevenson and his team at EJI have gotten creative in teaching as many people as he can about what’s at stake and how we can all help challenge the status quo.

In addition to his anti-poverty initiatives and the reports and studies EJI produces, EJI has also founded two new landmarks in historic Montgomery, Alabama, the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the only memorial to lynching victims in the country.

Courtesy of Just Mercy‘s studio Warner Bros., Shadow And Act traveled down to Montgomery to experience these landmarks in person.

Just a short walk from the Alabama River where stolen African people were transported from the river bank to the auction block (now memorialized with a fountain), you’ll find EJI and the Legacy Museum. There are no pictures, no videos allowed inside. It is a hallowed ground of reverence and remembrance. “You are standing on a site where enslaved people were warehoused,” read the white, spray-painted letters on the brick wall when you first enter the museum. The first exhibit drives this point home.

There is a row of cages replicating the ones enslaved Africans would have been held in back when the museum grounds were a warehouse. When you step up to one of the cages, a hologram comes to life—a child, a mother, a young man, a singing-to-get-by woman—and tells you their story. When they’re done telling their own story, they fade away, like ghosts at peace.

The weight of the ancestors continues on with you throughout the museum, which shows the through-line of slavery and present-day mass-incarceration, covering the whitelash to Reconstruction, and all of the white terrorism against Black people, including lynchings, Jim Crow laws, bombings, chain gangs, “convict leasing,” the so-called War on Drugs, the “superpredator children” propaganda which led to the kinds of mandatory sentencing for kids that Stevenson finally got overturned by the Supreme Court in 2012, and the exploding Black prison population of today.

In between a collection of jars containing dirt from known sites where Black people were lynched and a wall of letters written by people in prison, there’s a row of telephones and chairs in front of plexiglass. When you pick up the phone, a hologram of an incarcerated person—much like the enslaved people in the first exhibit—comes to life and tells you their story. With the phone to your ear, all you can do is listen. Like Stevenson’s grandmother used to always tell him, “You’ve got to get close…”

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is just a short drive away from EJI and the Legacy Museum. It sits atop a hill on Caroline Street in downtown Montgomery. The walkway from the entrance beginning at the base of the hill is lined with a wall that holds information to contextualize the white terrorism of Black people in the post-Reconstruction Era. Nearly 4,400 lynchings of Black people in America have been documented by EJI and other researchers, the words on the wall explain. But nothing prepares you for the actual experience of the memorial.

When you reach the (wheelchair-accessible) top of the hill and enter the memorial, the rectangular slabs of steel—which document the county, state, known dates and names of lynching victims—the tombstone-like monuments are connected both to the ceiling by steel pipes, and to the ground. But then, you keep walking. Ever so slightly, the tombstones raise off the ground—an inch or two, a foot. When you turn the first corner inside the memorial, the weight of it is fully realized. As the ground angles downhill, the monuments are suspended in the air, like the stolen victims they represent, until they are hanging far above your head.

There is a balm for the harrowing experience on the ground floor of the memorial, a wall of cleansing water to blend in with the tears. The words before the waterfall read:

“For the hanged and beaten. For the shot, drowned, and burned. For the tortured, tormented, and terrorized. For those abandoned by the rule of law. We will remember. With hope because hopelessness is the enemy of justice. With courage because peace requires bravery. With persistence because justice is a constant struggle. With faith because we shall overcome.” [emphasis added]

If you can last this long, the breaking point comes at the exit to the memorial at the sight of this Toni Morrison quote from Beloved on the wall:

“…And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck, put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up. And all your inside parts that they’d just as soon slop for hogs you got to love them. More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. Hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize.”

Art As Activism

On my second time through the Lynching Memorial—dry-eyed, this time, after the healing cry—Stevenson walked with me. While the average person may not understand his complicated Supreme Court victories and their ramifications, they will undoubtedly understand slabs of steel monuments hanging from the ceiling above them, a sculpture of enslaved people and children in chains, a Toni Morrison quote, a haunting hologram. I asked Stevenson when he first understood the power of art as activism in line with his legal work.

“I think I’ve always been aware of it but hadn’t really applied it,” he said as we walked up the hill to the memorial. “I grew up in a community where our pain and our grief and our suffering would get expressed through music. And I would listen to music; it was a safe place to retreat when you were trying to manage things and process things. But it’s only recently that I’ve started thinking intentionally about how we have to use art to get people to engage.”

On the way up the hill, as we stood in front of the sculptures of enslaved people in chains by the artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Stevenson explained, “We started thinking about ways to construct visuals that help people understand this. The book and now the movie are just new ways to use the creative talents that extraordinary people can give to a project that’s trying to just help people understand things.”

With that understanding comes a call to action.

“You see my clients, you see their families and you see the suffering that is created when we’re unjust and we’re unfair. And I hope seeing that suffering and that pain will motivate people to want to demand more justice, demand more fairness.”

As for how to begin making these demands, Stevenson has a plan:

“There are multiple ways that people can participate in the effort at recovering from all of this injustice. They can support people coming out of jails and prisons. They can get active on the multiple campaigns going on around the country to respond to injustice and wrongful convictions. They can make the journey here to Montgomery because we think it’s important for people to spend time in these places. They can learn who their prosecutors are and make sure that those prosecutors are representing their values and their expectations for how justice should happen in their community,” he said.

“I think we should be calling for the elimination of these immunity laws that I think have insulated so much bad behavior by police prosecutors and judges. I think we need our elected officials to be called out whenever they engage in this kind of fear and anger narrative that has created the environment that made it so easy for people like Walter McMillian to be wrongly convicted. And then finally, I think we have to deal more honestly with our history of racial injustice. Black and brown people are presumed guilty and that has to change and it won’t change until we’re able to talk more honestly about racial injustice.”

Another Possible World

But most of all, Stevenson is asking us all to consider a radically different approach to justice, one that centers the needs of those in poverty, without access to resources and without hope. His approach requires us to be more invested in healing the why, the conditions that caused the harmful behavior, rather than a fixation on punishment and disposal of the most vulnerable members of our society.

“I don’t think we prove how great we are, how just we are, how advanced we are by looking at how well we treat the rich and the powerful and the privileged. I think we have to look at how we treat the poor and the incarcerated and the condemned. I think that’s the lens through which we have to judge ourselves.”

After more than 30 years of this work—with clients lost to death row, people still incarcerated for life for crimes they committed as children and the apathy and willful ignorance of so many in our society to the crimes of our legal system—Stevenson still maintains the mantra emblazoned on the wall at the lynching memorial, “Hopelessness is the enemy of justice.”

As the monuments hung above our heads, Stevenson shared how the city he’s made his home helps him to maintain his hope.

“That’s the best part about living in a place like Montgomery, Alabama,” he said. “I’m standing on the shoulders of people who did so much more with so much less. The people [who were] trying to do what I’m trying to do today, 60 years ago had to frequently say, ‘My head is bloodied but not bowed.’ I’ve never had to say that. And I know that it was their hope for an end to segregation which created the opportunities for me to even be representing the clients that I’m representing, [to] be in those spaces where I have to navigate some of that frustration,” he said.

“And I just believe that that is my obligation, to continue to believe things I haven’t seen, to imagine another world, another future for the next generation, where the burdens are less, where the inequality is less, where the injustice is less,” Stevenson said.

“And that sustains me. That energizes me. That makes it possible to do the hard things.”

Just Mercy opens in limited release on Christmas Day 2019 and everywhere on January 10, 2020.

READ MORE:

WATCH: New ‘Just Mercy’ Trailer Further Showcases This Real-Life Fight For Justice