To Sleep With Anger was released with a small bit of fanfare in 1990. Charles Burnett had already acquired a reputation as one of our most important homegrown auteurs even if most of the audience, black and white alike, were unfamiliar with his work.

The film was released at something of an apex for Black American Cinema (and Black American Pop Culture in general). Do The Right Thing had only been released a year before, Boyz N The Hood was less than a year away; new black auteurs were appearing every year with a mandate to be successful and say something authentic about our experience in this country. Heady times.

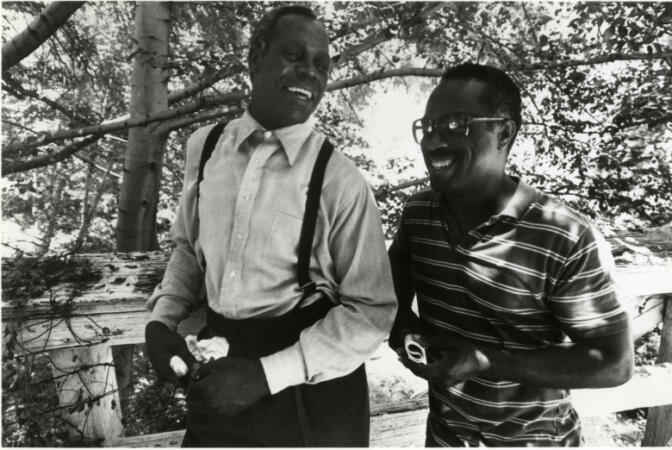

Danny Glover had appeared months earlier as the lead in a Predator sequel and he was still an A-lister with both a string of mainstream hits and street cred as both an actor’s actor and a man of integrity. He used this muscle to help Charles Burnett make this sly film about everyday black folks in Los Angeles, a film that speaks softly but speaks volumes.

To Sleep With Anger has been somewhat forgotten. Burnett’s first masterpiece Killer of Sheep has gotten all the attention for its beautiful black and white photography and Neo-Realist approach. Add to that a spotty DVD release (the film is not currently available on either disc or streaming on Netflix) and it’s no wonder To Sleep With Anger has become the Jan Brady of Burnett’s output.

And that is a pity. To Sleep With Anger is every bit the masterpiece that Killer of Sheep is and the ways they differ from one another are fascinating. Both are family dramas set in Black Los Angeles about everyday folk who are neither hoodrats nor the Talented Tenth.

But where Killer of Sheep tells its story with a strict sense of Neo-Realist naturalism, To Sleep With Anger boldly declares itself a parable during its opening credit sequence. Like Fellini decisively breaking with his Neo-Realist past with the opening of 8 ½ , Burnett similarly throws down the gauntlet with symbolic imagery that’s hard to forget.

The story focuses on a family with two grown sons, both married with children. The patriarch Gideon (Paul Butler who at the time I knew from Michael Mann’s TV series Crime Story) and his wife Suzie (played by Mary Alice, mostly known for A Different World) are, like almost all Black Angelenos of their generation, transplants from the South. Their lives and the lives of their sons are fairly normal, though it is clear there are tensions brewing between elder son Junior (played by Carl Lumbly) and his baby brother, known to all as Baby Brother (played by Richard Brooks).

And then comes the catalyst. Danny Glover’s Harry Mention turns up like a figure out of folklore. He is an old friend of Gideon and Suzie’s from Down Home. It is hard to do justice to the size and scope of Harry Mention as a character and Glover’s bravura turn which has to be his best work on film.

Let it suffice to say that Harry is not what he seems to be on first meeting. He plays the simple man but quotes Pushkin, he seems to symbolize the power of tradition but describes himself as a modern man. He is a truth-teller at times, an instigator at others. He’s Iago, he’s Falstaff, he’s wholly original and yet vaguely familiar.

Like all great art, To Sleep With Anger triumphs because it works both on a personal level (it almost feels like theater at times, like August Wilson if he didn’t try so hard) and it is provocative enough thematically to fuel hours of discussion about tradition versus modernity and how it has affected African-Americans, for better or worse.

Tradition versus modernity is just one of the many dichotomies Burnett is exploring in To Sleep With Anger. He’s asking us to think about the generation gap, Christian faith versus backwoods mysticism, the grip of the past versus the pull of the present, African-American yearning for financial prosperity versus our sense of altruism & duty and complications within both sides of each coin.

Spike Lee may have ruled the day with his provocative brand of cinema and his controversial (to some) statements, but Burnett (his antithesis in so many ways, and also his superior) got rave reviews for To Sleep With Anger, as well as Independent Spirit Awards for screenplay and direction, Best Actor for Glover, and Best Supporting for Sheryl Lee Ralph as Baby Brother’s hapless bougie wife. Other awards were given by the Sundance Film Festival and National Board of Review.

We shall be judged harshly and unfavorably one day for the neglect we (as Americans, and specifically as Black Americans) have doled out to Mr. Burnett. His recent rousing widescreen national epic for Namibia (starring Carl Lumbly) didn’t even get a week long engagement at the Nuart. This reflects more poorly on us than Mr. Burnett.

It also makes the slow fading of To Sleep With Anger from collective memory such a bitter pill. The film has just as much to say now in the Age of Madea as it did in the Age of Spike. And if we have any wisdom, we’ll listen.